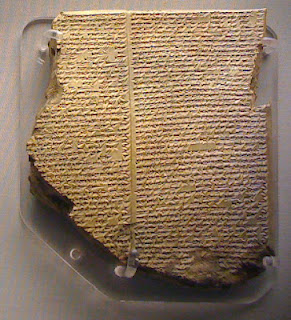

Undoubtedly the Hebrew scribes who were exiled in Babylon a hundred years later would have encountered writings such as this... and that, of course, brings us on to the thorny subject of Biblical Literalism. It dawned on me a few weeks ago that the notion that Christianity begins and ends with the Bible is a relatively recent invention. Christianity is 2000 years old, but Biblical Literalism (as a widespread concept) can be no more than 500 years old. Printing, in the context of European culture, was only invented in the 15th century, before which Bibles were rare and expensive hand-written manuscripts. They were written in Latin, too, so most people wouldn't have been able to read them even if they'd got their hands on a copy.

In its early days, Christianity was typical of the religions of its time. Religions in those days were centred, not on writings, but on symbolism and ritual... a wide variety of rituals, but all of them in one way or another aimed at personal transformation. This was true, in broad terms, of the Mystery religions of Graeco-Roman Europe as well as the "Eastern" religions of Persia and India. While there are great differences of detail, the basic concept was much the same. Writings, if they existed, were for the priesthood, not the people... and usually they were meant for guidance only, not as a central focus of belief.

Early in the 5th century AD, St Augustine wrote a treatise called "The Literal Meaning of Genesis"... but he was arguing for a symbolic, spiritual interpretation of that work, not a literal interpretation in the modern sense. Augustine's mother was a Christian, but in his early years he turned to another Mystery religion of the time, Manichaeism, before converting back to Christianity. So he was able to look at Christianity from an outsider's perspective, and see that people who insisted on the word-for-word truth of the Bible were merely making themselves look stupid: "Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world... If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on facts which they themselves have learnt from experience and the light of reason?"

The notion that Christianity should be centred on the Bible, and not on its rituals, originated in 16th century Europe, as more and more people gained access to affordable copies of the Bible in a language they could understand. This was a brand new type of religion... one that belongs to a period in which books are common and everyone can read. That simply wasn't the case when Christianity started out.

The English Puritans of the 16th and 17th century were amongst the earliest Biblical Literalists. They were persecuted by the established churches (both the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England), and to escape this persecution many of them emigrated to America, where they were among the first European settlers. In some sense, therefore, America is founded on Biblical Literalism. That's probably why most people in the English-speaking world today (atheists just as much as Christians) see Biblical Literalism as the "purest" form of Christianity. That may be true... but the fact remains it's only a quarter the age of Christianity as a whole!